Five new species of eyelash vipers discovered in Colombia and Ecuador

Published February 8, 2024.

A group of scientists led by researchers of Khamai Foundation discovered five dazzling new species of eyelash vipers in the jungles and cloud forests of Colombia and Ecuador. This groundbreaking discovery was made official in a study published today in the open-access journal Evolutionary Systematics.

Prior to this research, the captivating new vipers, now recognized as among the most alluring ever found, were mistakenly classified as part of a single, highly variable species spanning from Mexico to northwestern Peru. The decade-long study initiated with an unexpected incident wherein one of the authors was bitten by one of these previously undiscovered species.

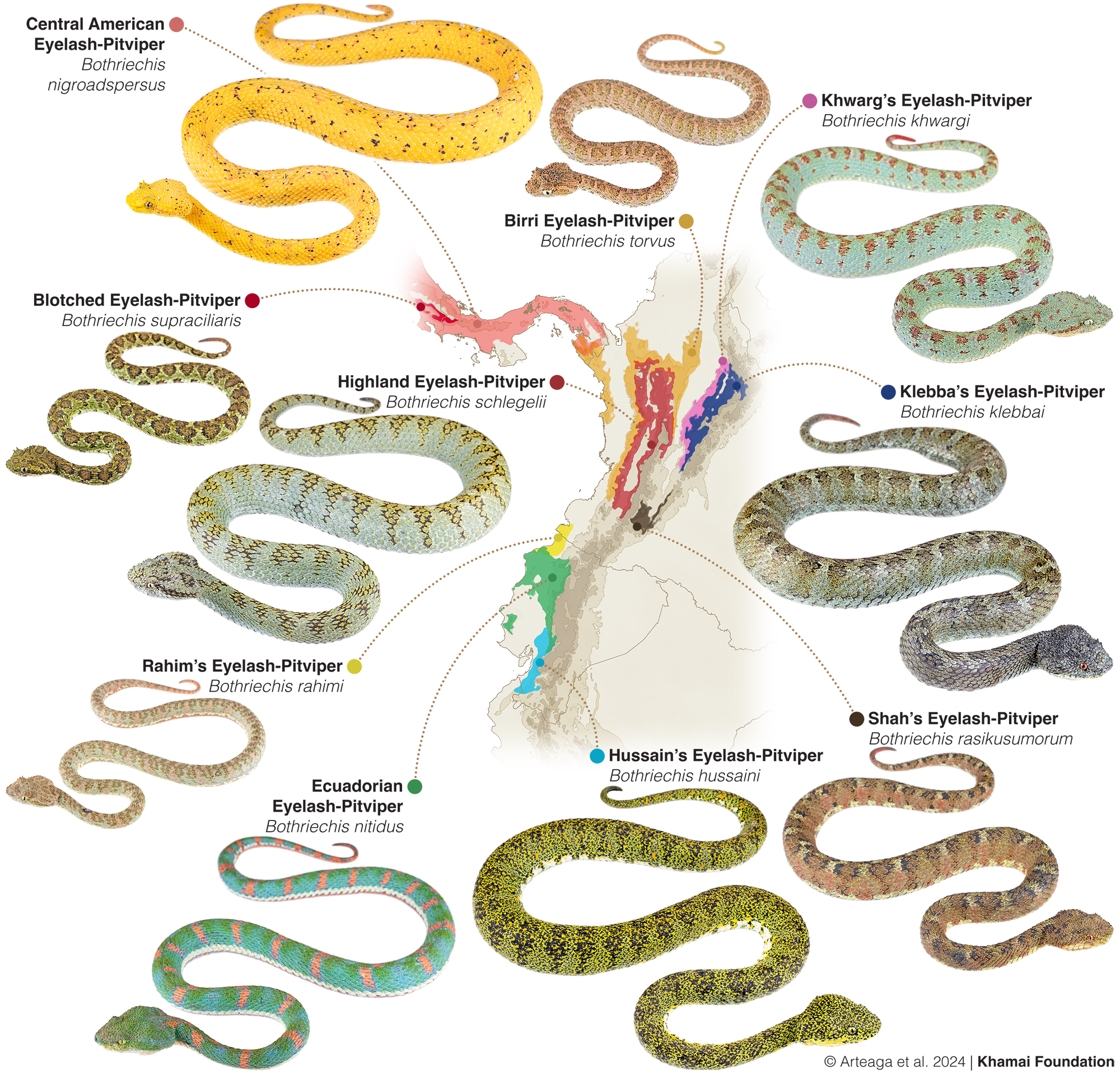

Figure 1. Distribution of the palm pitvipers of the Bothriechis schlegelii species complex, including the five new species described in Arteaga et al. 2014.

What’s different about these eyelash vipers?

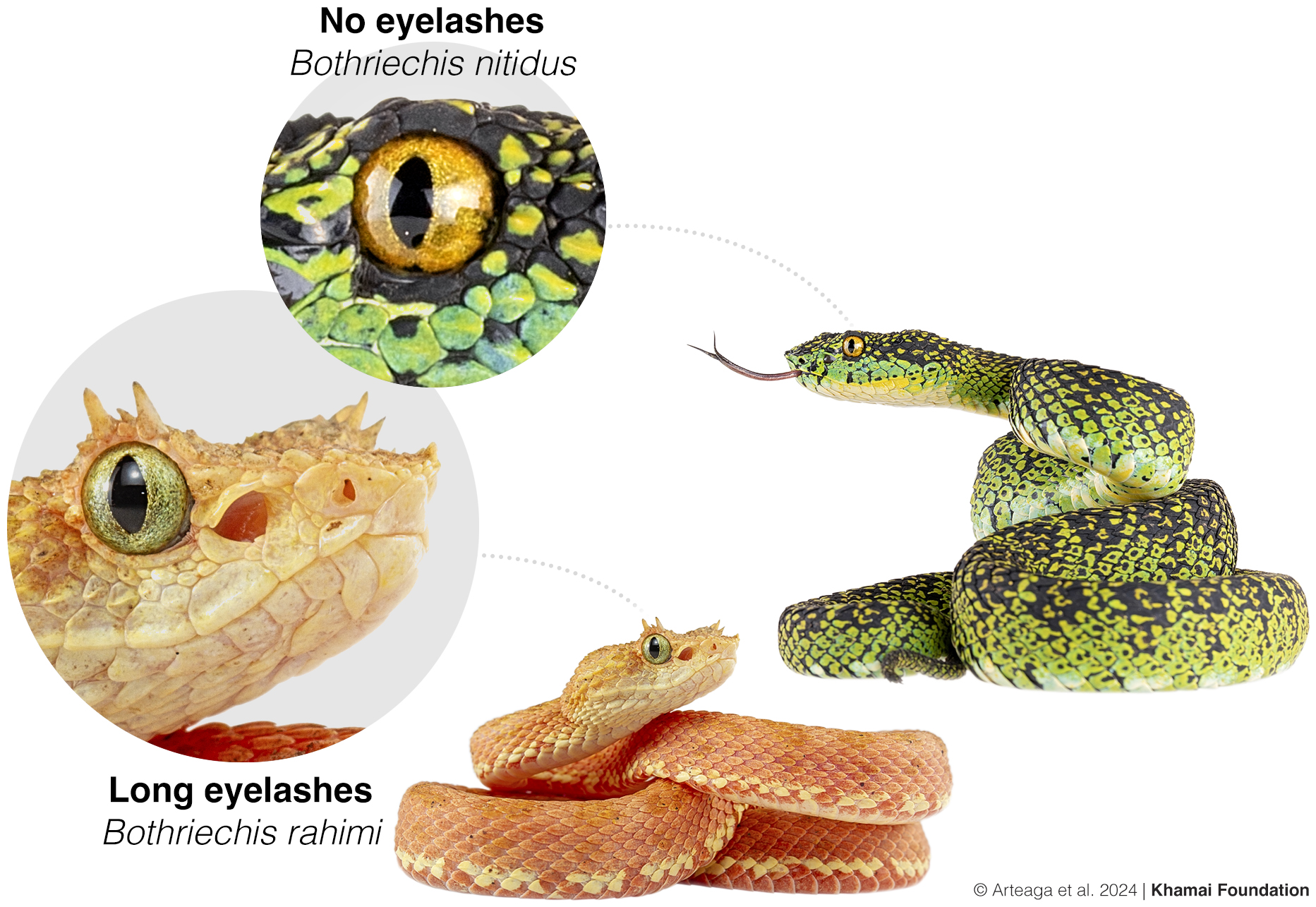

Eyelash vipers stand out due to a distinctive feature: a set of enlarged spine-like scales positioned atop their eyes. These “lashes” bestow upon the snakes a formidable and fierce appearance, yet their true purpose remains unknown. What is definite, however, is that certain populations exhibit longer, and more stylized eyelashes compared to others. The variations in the condition of the eyelashes led researchers to hypothesize the existence of undiscovered species.

Figure 2. The clue that led the researchers to suspect that there were new species of eyelash vipers was the fact that some populations in the cloud forests of Ecuador had almost no “lashes.” Photos by Lucas Bustamante and Jose Vieira.

Eyelash vipers are also famous for another feature: they are polychromatic. The same patch of rainforest may contain individuals of the turquoise morph, the moss morph, or the gold morph, all belonging to the same species despite having an entirely different attire. “No two individuals have the same coloration, even those belonging to the same litter (yes, they give birth to live young),” says Alejandro Arteaga, who led the study.

For some of the species, there is a “Christmas” morph, a ghost morph, and even a purple morph, with the different varieties sometimes coexisting and breeding with one another. The reason behind these incredible color variations is still unknown, but probably enables the vipers to occupy a wide range of ambush perches, from mossy branches to bright yellow heliconias.

Figure 3. Yellow-pink morph of the Rahim’s Eyelash-Pitviper (Bothriechis rahimi). This species is named after Prince Rahim Aga Khan and stands out for occurring in remote and pristine rainforests currently controlled by drug cartels at the border between Ecuador and Colombia. Photo by Alejandro Arteaga.

Figure 4. The Rahim’s Eyelash-Pitviper (Bothriechis rahimi) is considered a Vulnerable species because its extent of occurrence is estimated to be much less than 20,000 km2 and its habitat is severely fragmented and declining in extent and quality due to deforestation. Photo by Lucas Bustamante.

Figure 5. Black-and-yellow morph of the Hussain’s Eyelash-Pitviper (Bothriechis hussaini). This species is named after Prince Hussain Aga Khan, who has devoted his life, influence, and wealth to environmental conservation since he was eleven years old. Photo by Alejandro Arteaga.

Figure 6. Brown morph of the Shah’s Eyelash-Pitviper (Bothriechis rasikusumorum). This species is named after the Shah family. It is endemic to Huila department in southeastern Colombia, where it inhabits montane cloud forests and coffee plantations. Photo by Jose Vieira.

Figure 7. “Coffee” morph of Bothriechis klebbai. This species is named after Casey Klebba, who co-founded MiniFund with Carly Jones to preserve tropical biodiversity. It is endemic to the Cordillera Oriental in eastern Colombia. Photo by Elson Meneses.

Where do these new snakes live?

Three of the five new species are endemic to the eastern Cordillera of Colombia, where they occupy cloud forests and coffee plantations. One, the Rahim’s Eyelash-Pitviper, stands out for occurring in the remote and pristine Chocó rainforest at the border between Colombia and Ecuador, an area considered “complex to visit” due to the presence of drug cartels. The Hussain’s Eyelash-Pitviper occurs in the forests of southwestern Ecuador and extreme northwestern Peru. The researchers outline the importance of conservation and research in the Andes mountain range and its valleys due to its biogeographic importance and undiscovered megadiversity.

Figure 8. The Chocó rainforest is home to four vipers of the Bothriechis schlegelii species complex, including two new species discovered by Arteaga et al. 2024. Photo by Lucas Bustamante.

Figure 9. The researchers discovered three of the new species of Bothriechis in the cloud forests of the Cordillera Oriental of Colombia. Photo by David Jácome.

What’s with the venom?

“The venom of some (perhaps all?) of the new species of vipers is considerably less lethal and hemorrhagic than that of the typical Central American Eyelash-Viper,” says Lucas Bustamante, a co-author of the study. Lucas was bitten in the finger by the Rahim’s Eyelash-Pitviper while taking its pictures during a research expedition in 2013. “I experienced intermittent local pain, dizziness and swelling, but recovered shortly after receiving three doses of antivenom in less than two hours after the bite, with no scar left behind,” says Bustamante.

Figure 10. Researcher Alejandro Arteaga examines the fangs of Central American Eyelash-Pitviper (Bothriechis nigroadspersus) in the Darién jungle of Panamá.

Figure 11. The study was based on examination of 400 museum specimens of Bothriechis housed at zoological collections in United States, Germany, Austria, Colombia, Ecuador, Panama, and France. Photo by David Jácome.

Who is honored with this discovery?

Two of the new species of vipers, the Rahim’s Eyelash-Pitviper (Bothriechis rahimi) and the Hussain’s Eyelash-Pitviper (B. hussaini), are named in honor of Prince Hussain Aga Khan and Prince Rahim Aga Khan, respectively, in recognition of their support to protect endangered global biodiversity through Focused On Nature (FON) and the Aga Khan Development Network. The Shah’s Eyelash-Pitviper (B. rasikusumorum) honors the Shah family, whereas the Klebba’s Eyelash-Pitviper (B. klebbai) and the Khwarg’s Eyelash-Pitviper (B. khwargi) honor Casey Klebba and Dr. Juewon Khwarg, respectively, for supporting the discovery and conservation of new species.

Figure 12. Red-wine morph of the Central American Eyelash-Pitviper (Bothriechis nigroadspersus), photographed in the Caribbean Island Escudo de Veraguas, off the coast of Panamá. Photo by Alejandro Arteaga.

Figure 13. Turquoise morph of the Ecuadorian Eyelash-Pitviper (Bothriechis nitidus). This species is endemic to the Chocó rainforest in west-central Ecuador. Photo by Alejandro Arteaga.

How threatened are these new species?

One of the study’s key conclusions is that four of the species in the group are facing a high risk of extinction. They have an extremely limited geographic range and 50% to 80% of their habitat has already been destroyed. Therefore, a rapid-response action to save the remaining habitat is urgently needed.

What is next?

Khamai Foundation is setting up a reserve to protect a sixth new species that remained undescribed in the present study. “The need to protect eyelash vipers is critical, since unlike other snakes, they cannot survive without adequate canopy cover. Their beauty, though worthy of celebration, should also be protected and monitored carefully, as poachers are notorious for targeting charismatic arboreal vipers for the illegal pet trade of exotic wildlife,” warns Arteaga. Finally, he and his team encourage the support of research on the venom components of the new species of vipers. This will promote their conservation as well as help communities that regularly encounter eyelash pitvipers.